Discover the brands and technologies from our business units Henkel Adhesive Technologies and Henkel Consumer Brands.

The palm path out of poverty

Editor’s note: This article was update on April 7, 2021.

Oil palm farming has massively improved the quality of life of smallholder farmers in northern Honduras. But rapid change has also created challenges related to ensuring environmental responsibility, safe working conditions and strong relationships across communities. The solution? Training in best practice and open communication along the entire value chain and creating an effective policy environment for sustainable palm cultivation.

In the early 1970s, Fausto Martínez left his home in the Lenca community of Guajiquiro, Honduras, to search for a job. Without proper schooling and unable to read or write, the only place Fausto could find work was on the banana farms more than 300 kilometers to the north east. The work gave him an opportunity to learn about agriculture – but working conditions were poor because labor laws supporting workers’ rights were almost never enforced. “But it was a job,” Fausto says.

At the end of 1974, Hurricane Fifi-Orlene hit northern Honduras. It was the worst natural disaster Honduras had ever seen, wiping out the country’s entire banana crop and erasing communities overnight. The livelihoods of tens of thousands of Hondurans like Fausto were completely destroyed.

One year later, the Honduran government responded to decades of protest by the Honduras Farmworker Movement by introducing its Agrarian Reform act. This legislation aimed to address living and working conditions within the country’s banana industry. “Those were very difficult years,” recalls Fausto. “We tried to grow rice, corn and other crops, but that doesn’t pull anyone out of poverty.”

Betting on oil palm

The leaders of the Farmworker Movement pushed for new projects with crops that had the potential to improve their quality of life. After unprecedented debate among the farming community, oil palm was chosen. It was a decision that would transform the entire region – as well as the living conditions of its communities and farmers.

“The beginning was very difficult because there was no confidence,” Fausto continues. “Working collectively is not for everyone: Many felt that others were taking advantage of them, that they were working for someone else. When our first harvest was sold at miserable prices, we saw the need to process our own fruit in order to add value to our produce. With support from the Netherlands, we obtained an extraction plant in 1985. That’s when we began to see some change in our lives.”

Joining together with people from across the smallholder community, Fausto became one of the founders of Hondupalma – an organization that represents 31 associated groups and hundreds of independent partners and producers. It now owns a refining plant, a fractionating plant, a churn plant and an almond plant, as well as a tank for oil exports, a boiler with a turbine for power generation and equipment for biodiesel generation. “If you didn’t see it, you would never believe how far we’ve come in these 35 years,” Fausto says.

“If you didn’t see it, you would never believe how far we’ve come in these 35 years.

Fausto Martínez, Smallholder Palm Oil Farmer

Rising to meet new challenges

There are approximately 20,000 smallholders in the northern zone of Honduras and, like Fausto, they each saw oil palm as an opportunity to move themselves and their families from poverty to prosperity. When the farmers began making a profit, they also became aware of additional factors that they needed to take into account – including environmental responsibility, workers’ rights and community relationships.

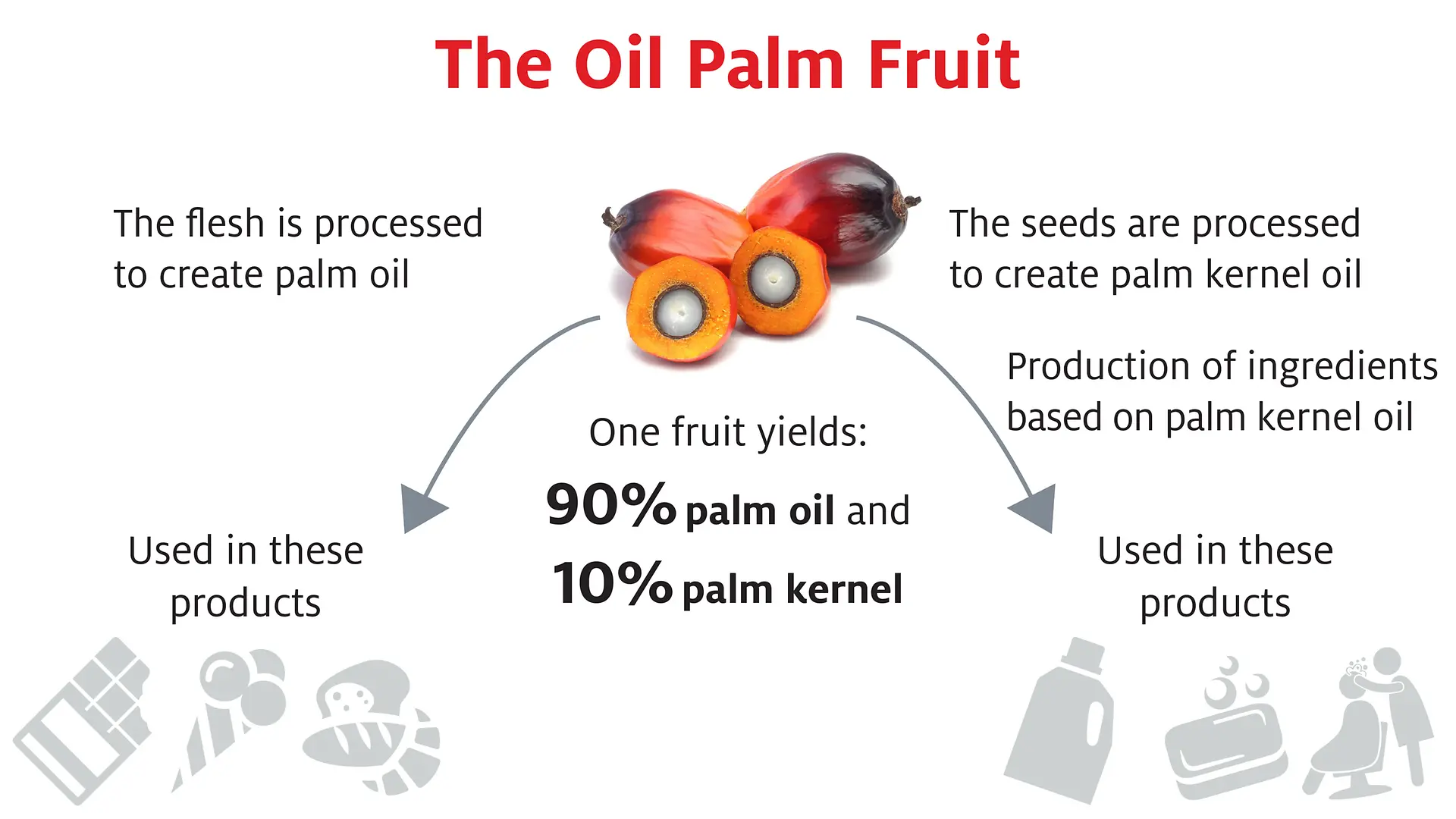

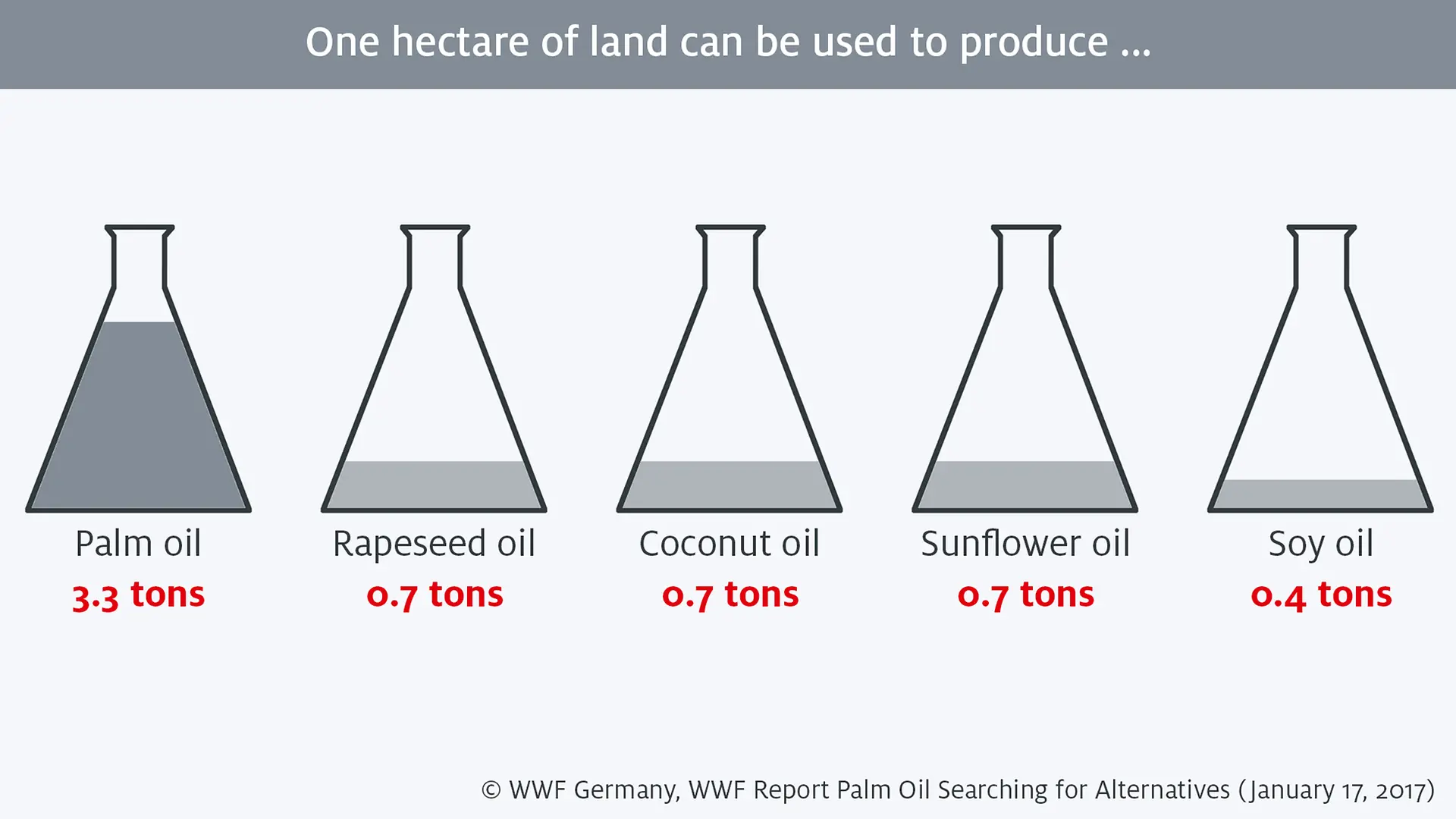

In particular, oil palm smallholders in Honduras needed to take action to ensure high-quality, sustainable production. While the oil palm tree is much more productive than other vegetable crops, the palm oil industry has been linked with negative impacts on the environment, as well as on people living and working in communities affected by its activities.

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) offers an established certification program for palm oil and palm kernel oil that covers criteria ranging from deforestation through to workers’ rights. However, certification is not enough to drive industry transformation. That’s why the government of the Netherlands joined together with the consumer goods company Henkel and the international civil society development organization Solidaridad in 2012 to promote the RSPO standard in Honduras.

Empowering smallholders through training

Initially, these partners found that the farming community needed substantial technical support and that there was a severe lack of communication among stakeholders across the supply chain. By working together, Solidaridad and Henkel supported projects that provided smallholder farmers with training in modern agricultural techniques for growing oil palm trees. This empowered the farmers to increase productivity and meet rising expectations for safety and environmental sustainability. It also ensured employment stability and improved livelihoods for workers and their families.

Changing people’s lives by changing their mentality

Palm oil is a controversial commodity that presents significant challenges – which is why many people and organizations initially react by trying to avoid it. However, Solidaridad and Henkel are convinced that it is possible to drive progress toward sustainability in this industry by directly working together with smallholders and communities. In fact, the two partners are aiming to support 100 percent of the producers in this region in becoming RSPO certified, while also looking beyond certification and toward achieving sustainable landscapes.

Changing the mentality of people takes time. But we must not stop. The key is not to prohibit their products, but to support them in improving the way they produce them.

Flavio Linares, Technical Head of Programs, Solidaridad Central America

“It’s important that people understand that in a country like Honduras, where the agricultural model is based on smallholder cooperatives, the economic spillover has a great impact on the livelihoods of many people,” says Omar Palacios, Solidaridad Country Director for Honduras. “Changing the mentality of people takes time. But we must not stop. The key is not to prohibit their products, but to support them in improving the way they produce them.”

A model that makes a difference worldwide

The oil palm sector in Honduras has now become a regional leader. It provides a model for how the private sector, cooperatives and local government can work together to implement better policies quickly and effectively – and this model is now being applied to other commodities across Honduras and the region as a whole. For example, the positive impact on producers in Honduras enables Solidaridad to upscale activities regionally, by promoting a similar innovative and inclusive smallholder approach in Nicaragua.

I’ve met so many people and heard so many ideas. And although I never learned to read or write, oil palm has allowed me to educate my five children. Maybe learning to learn will be the most valuable lesson for all of us.

Fausto Martínez, Smallholder Palm Oil Farmer

After working in agriculture for almost 40 years, Fausto was able to buy some land of his own. Five years later, he now owns 21 hectares of land (53 acres) for oil palm, banana, plantain and cacao agroforestry. “The most relevant change I’ve seen is the cultural change,” Fausto says. “I realize now that most of the time people do things the same way because no-one has told them that there’s a better way to work the land, use the resources and talk to each other. I’ve met so many people and heard so many ideas. And although I never learned to read or write, oil palm has allowed me to educate my five children. Maybe learning to learn will be the most valuable lesson for all of us.”